This is a dingy way to die.

—Malcolm Lowry

In purgatory, there are nine seas. Little Leini washed up in the first of them on the bumper of a Baltimore transit bus on All Souls Day, 1989. Rain was falling hard and it was cold. Soaked to her Hellenic bones, she never saw it coming. From the other side of the street, staring through the plate glass window in front of his grill, Frangos the cook did.

A stoop-shouldered, late-in-middle age woman in traditional mourning black (despite never having been married) standing on the corner, waiting for a light she could not see to change. Frangos recognized her (something was wrong with her eyes) from Greek funerals; had heard stories about her and her mother since he was a kid. As she stepped off the curb to cross Eastern Avenue in the downpour — her head covered with a sopping copy of the Shopper’s Guide – Frangos ran out of his cafe, shouting.

“LIGO ELENI! LIGO ELENI! STOP!

She did not, nor did the bus.

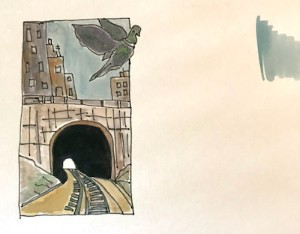

Nine minutes later, Little Leini was on the operating table and paddling through the world to come—one foot on the platform, the other on the train—at the same time.

Can you be a ghost if you are not yet dead? She’d never know for there are no answers in the great vestibule of the multiverse, just a door at each end.

Even in kathartírio her eyes resembled those of a flounder, either too far apart or too close together depending on which way she turned. Beyond the storm clouds, she tumbled through a tangled mess of man-made blight. More plastic than fish, the fish upside down and blind, a funhouse mirror reflecting the desecrated world of man. She landed upright before a skeleton standing watch at a sunken galleon – its hold once filled with the spoils of genocide but not as despoiled as the watchman.

He had pale gray pebbles for eyes, his ribcage a mossy aquarium, open to the seas. Ears mostly gone, but enough of the lobes remained for a cheap earring to hang from each. It made him look not so much like a pirate who’d walked the plank but a stubborn, middle-aged shrew who, tired of waiting, had crossed the street against the light.

At home, his name was Wayne, murdered with a crossbow in a Baltimore City drug deal gone sideways on his 30th birthday. On the streets, he was Wing Nut.

“Yo, fuckin’ Wing Nut caught an arrow in the neck on the parking lot of the McDonald’s. Bled out before I could get my nuggets.”

“No.”

“Yeah.”

By the time Little Leini encountered him—raining on Earth, raining in purgatory, raining below the sea—the fiend had been stripped of flesh, organs, and what little gifts bestowed at birth, all except a rusty skill to persuade, wheedle, and cajole. He would have made a great salesman except that he was always buying. For his transgressions, Wayne had lost everything but the memory he’d long tried to anesthetize in the upper world. It remained vivid; painful and acute. Somehow, he knew Little Leini’s legal name—Eleni Chrisoula Papageorgiou—and pronounced it in perfect Greek.

But she was not a Papageorgiou, she was a Pound, the only issue of a storied horse-and-wagon junkman; Little Leini fathered by Orlo Pound in 1949 with Leini Papageorgiou, who, at the age of eight, had been traded from the island of Samos to a childless couple on the Baltimore waterfront for fourteen sewing machines.

“Pound” was also jailhouse slang for five years in the joint, which the Nut had done twice before the arrow—not much more than a toy—pierced his esophagus. It was held in place now by his earthly duplicity and mimicked an ear-to-ear grin as he bid his most recent mark to make herself at home.

Little Leini had never been especially bright, but she wasn’t a dummy either, having learned most of what she knew about life from watching the construction of the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel when she was 11-years-old (standing behind the fence as they dug it out) and pestering her mother for years about the junkman.

Wing Nut, again: “Welcome.”

“To where?”

“Here.”

“Where is here?”

“The place where you wait.”

Little Leini’s flounder eyes—the stigmata of her birth, frightening drunks on the street and little kids—were weaker than those of the fish. But down below the waves (the place where you wait, the first rung of atonement, almost dead with no guarantee of not becoming forever dead), her eyesight was perfect. Which would have benefited her at the corner of Eastern and Eaton. Now they focused on Wing Nut’s ribs and she was dying to run her fingertips across them.

The fibers looked like the softest fur. Like her own pubic hair, which no one but herself had ever touched; once silky and now coarse, like the hair that grew above her lip and around her nipples.

How badly he wanted her to touch them, how good to be near anyone with even the dimmest spark of life, feeling the heat of temptation along the ribs closest to where his heart had been. In an eternity or two, the moss and lichen covering Wing Nut’s bones would become barnacles, strong enough to bolt him in place for eons beyond that.

He strummed his finger bones up and down his ribcage like a rounder in a jug band with a song he never learned: “Down below Atlantis, tombstones and soggy bones; these old evil blues keep poundin’ me, Davy Jones pillow my God-forsaken home …”

Little Leini applauded. He coveted her hands and asked, “Do you know the difference between moss and lichen?” She barely knew the difference between a fig and a fig newton.

“Go ahead,” he said, like a kid playing you-show-me-yours-I’ll-show-you-mine. “Touch it.”

It sounded too much like her earliest memory and she resisted. Instead, clasping her hands behind her back, she leaned in close enough to smell the stink wafting off of the colors: yellow, brown and purple cilia vibrating ever so slowly in the shade of the deep; a cocktail of moss and fungi and algae turning to crust, reproducing without sex, seed or flower. It would one day be a new suit of useless flesh for a kid who just couldn’t listen.

But maybe not. For it might just be that he’d finally found someone more broken than himself.

“Go ahead,” he said, laboring to push his ribs against her nose. “I don’t mind.”

• • • • • •

Little Leini had not been spared by the No. 29 bus to the meatpacking plant down the road, but it was the God of the Next Right Thing—“I was there, right there with you on the corner, but you were too busy counting your sins to know it—that saved her from the wiles of Wing Nut.

Just as Wing Nut’s ribs were about to brush up against her lacerated face—ever so close, by degrees smaller than the hairs of the moss that beguiled her. . . .

BANG!

Little Leini was again on the operating table (and in tremendous pain) at City Hospitals, the former grounds of the public asylum for the feeble-minded, deep in the bleeding heart of the Holy Land.

“She’s back,” said the nurse.

“We’ve got her now,” said the surgeon, who was long familiar with the odor of exposed organs but had never known any quite as pungent as the punctured lungs, spleen, and liver in front of him.

Little Leini spoke in an indiscernible garble with a tube down her throat: “Where am I?”

Her surrogate saviors did not hear so there was no way for them to tell her that she’d returned to the narrow streets and alleys of Baltimore—a bar at one end of every block, a church on the other, anything possible in between—to become a living ghost whose only life she’d ever haunt was her own.